Virtuality and Air, 2005

Does virtual space have some kind of atmospheric materiality that is, perhaps, something like air?

Introduction

In my previous post Thinking about Gaston Bachelard and the poetics of the network (2004) I recalled my endeavours to make sense of the internet as a space. This week I’m sharing another attempt to understand that strange world. It began as a presentation I gave in 2005 at ‘Altered States’, held at the University of Plymouth. It was one of a series of conferences curated by the cybernetic artist Roy Ascott. My presentation later became a paper and was published by The Liquid Press. This introduction is taken from the abstract for that paper.

Most visualisations of the internet are created from router nodes. There are many maps showing this flow of data in numerous variations. But what lies between these nodes? Does virtual space have some kind of atmospheric materiality that is, perhaps, something like air?

According to transfer protocol, the data doesn’t ‘leave’ node 1 until after it has ‘arrived’ at node 2 so in a sense it’s not going anywhere at all. Another interpretation is that since data travels at the speed of light, any time taken occurs not during the journey itself but is added in by the routers and modems which process them. But then, in a further contradictory complication, it could be said that the data is indeed travelling, only not in a physical sense, but inside an ‘internet cloud’.

According to the Zen Buddhist monk and teacher Shunryu Suzuki

‘When we inhale, the air comes into the inner world. When we exhale, the air goes out to the outer world. The inner world is limitless, and the outer world is also limitless. The air comes in and goes out like someone passing through a swinging door.’

To paraphrase Suzuki, perhaps what we call ‘I’ is just a swinging door which moves when we write or read into the virtual space of the internet. There’s no doubt that the ‘internet cloud’ is the most intensely compelling environment of the contemporary world. Is virtuality, like air, simply a property of the encompassing world in which humans – like all other beings – participate? That is the question behind this essay written twenty years ago. Does it make any sense in 2025?

Virtuality and Air

If there is any one place which allows me to penetrate the body of the internet, it is the FTP1 window. Two worlds lie within it - on the left, the inside of my computer. Every single directory, and all of their contents, can be inspected. Every love letter, every photograph, everything inside the trash bin. On the right, a new window opens to display another set of directories, but this time in an entirely different machine. These directories are located on a server in an air-conditioned vault somewhere in the state of Virginia. I reach into the right-hand window for the index.htm file and pull a copy of it over onto the desktop of my own machine. Effortlessly it glides from America to England, bypassing sea and air in between, requiring no stamps, no passports, no visas.2

This excerpt from my 2004 memoir Hello World: travels in virtuality describes a typical user’s experience of File Transfer Protocol. It feels as if one is transcending physical geography but in fact the transfer is much less mysterious than it appears. Every time we move data around the net, whether it be sending an email, uploading and downloading files, calling up a webpage or one of many other operations, the item is broken up into small packets of about 40 bytes each and transported piece by piece from one router machine to the next. These individual journeys (hops) are part of a somewhat ponderous process whereby after each hop every packet must be checked in and a message sent back to the point of its origination confirming its safe arrival. When all the packets have arrived at their destination, the item is reassembled for access. The router machines through which the data packets pass are situated in locations around the world, and as such they could be seen as physical anchors, momentarily securing the electromagnetic data to specific points of latitude and longitude while they are checked and then releasing them for their next hop.

Most visualisations of the internet are created from these router nodes. The progress of the hops can easily be tracked using programs such as traceroute, which lists the time of each hop and indicates where internet traffic may be congested or redirected etc.

There are many maps showing this flow of data in numerous variations. But what lies between these nodes? When I throw a ball from me to you, we know that it passes through the air. When a data packet moves from one node to the next, what equivalent environment does it pass through? Does virtual space have some kind of atmospheric materiality that is, perhaps, something like air?

Air

I recently moved from living in a house in the country with a large plot of land and fields beyond it, to a fifth floor city apartment with a sunny balcony but, of course, no lawn or flowerbeds. My friend, the poet Catherine Byron, viewed it from that perspective perhaps peculiar only to poets and cried out ‘Now you have air for a garden!’ She did not know that she had unwittingly focussed on an element which had lately begun to interest me: what is the relationship between virtuality and air?

In Hello World I described my intense relationship with technology and the ways in which it blends with the natural. Such investigations do not cease with publication, and I continued to research the connections between nature and the digital. Some months after the book was published, I read philosopher David Abram’s description of coming eye-to-eye with a condor high in the Himalayas. Resting on a rock, he was idly rolling a silver coin across his knuckles when he realised that the glinting metal had attracted the attention of a condor which then flew towards him:

As the great size of the bird became apparent, I felt my skin begin to crawl and come alive, like a swarm of bees all in motion, and a humming grew loud in my ears. The coin continued rolling along my fingers. The creature loomed larger, and larger still, until, suddenly, it was there – an immense silhouette hovering just above my head, huge wing-feathers rustling ever so slightly as they mastered the breeze. My fingers were frozen, unable to move; the coin dropped out of my hand. And then I felt myself stripped naked by an alien gaze infinitely more lucid and precise than my own. I do not know for how long I was transfixed, only that I felt the air streaming past naked knees and heard the wind whispering in my feathers long after the Visitor had departed.’3

Although Abram is not writing about technology at all – indeed, quite the opposite - I found in his text a powerful resonance with the final pages of Hello World :

Virtuality is my landscape, my city streets, my forests and my plains. It goes on around me constantly, this swell of noise and interaction which I move through all the time. It is a perpetual and highly-textured terrain – just as a train passes by fields, houses, swamps and deserts, so do I pass through the online world, in it and of it, myself a part of the whole and always accompanied by the murmurs and shouts of others travelling through the same spaces. It creates the poetics of the network.

It is Bachelard’s immense cosmic house:

‘Winds radiate from its centre and gulls fly from its windows. A house that is as dynamic as this allows the poet to inhabit the universe. Or, to put it differently, the universe comes to inhabit his house.’45

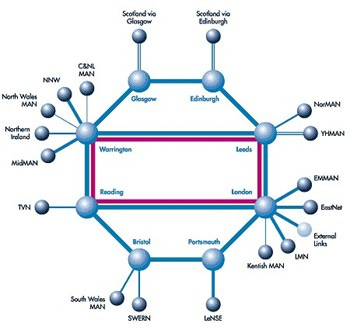

Abram’s book seems to begin where mine ended, with a sense of airy materiality. Much of my thinking about cyberspace has been about connecting the abstract with the meat, but recently I have begun to consider the invisible agency at work in these transactions. For many years I have been looking across the space and now I would like to look at the space itself. To date, I have conceived of it as an area strung with a cat’s cradle of lines across what is otherwise emptiness. My imagining was influenced by a number of different maps and visualisations of which the map for SuperJANET4, the UK academic computing network6, is a very typical example (Figure 1). There are many thousands of different maps available, depending upon the source data used to draw them, but I have chosen SuperJANET4 because not only is it simple to view but because the named UK cities help the reader to visualise the nodes in the network.

Figure 1: SuperJANET4

Each of the spheres in this diagram represents a router, or node. One imagines a user in, say, Bristol, accessing a website hosted within this system, for example my own site7 on a server at De Montfort University, Leicester. The Bristol user logs on to the network and enters a url into the browser, thus despatching a ‘fetch’ command via a node. The data packets then abseil from one point to the next across the wires or satellite signals (in this case they would travel via Leeds, since it is the nearest major node to Leicester) until the resource is located and served to the browser via the nearest node. The emptiness itself (shown in the SuperJanet diagram as unbroken lines and in the diagram below as …… ) has no agency other than to impose/create space between the points. Sometimes the emptiness contains a kind of weather, generated by the health of the network and external influences. The nodes are crucial, whereas the environment between them is at worst a hindrance, at best a null space.

User …… Browser …… Node …… Network …… Server …… Node …… Browser

But is it possible to turn that physicality inside out and instead to view the space itself as the major landscape and the nodes as mechanisms within it, acting as valves, osmotic membranes or perhaps even doorways? Such a scenario would generate a diagram something like Figure 2, where the emptiness (……) is manifested as an airy space within which the physical elements are distributed:

Figure 2

In The Absent Body Drew Leder recalls the words of Zen master Shunryu Suzuki:

When we practice zazen, our mind always follows our breathing. When we inhale, the air comes into the inner world. When we exhale, the air goes out to the outer world. The inner world is limitless, and the outer world is also limitless. We say ‘inner world’ or ‘outer world’ but actually there is just one whole world. In this limitless world, our throat is like a swinging door. The air comes in and goes out like someone passing through a swinging door. If you think ‘I breathe’, the ‘I’ is extra. There is no you to say ‘I’. What we call ‘I’ is just a swinging door which moves when we inhale and when we exhale.8

For users of wired internet, whether broadband or cable, the doorway is very clear – steps must be taken, wires must be plugged in, to facilitate connection to the internet. But for those operating in a wireless environment, there is no longer a doorway to be breached. Being connected is just as easy as – yes – it is just as easy as breathing. To paraphrase Shunryu Suzuki, what we call ‘I’ is just a swinging door which moves when we write or read into the virtual space of the internet. We say ‘online’ or ‘offline’ but actually there is just one limitless connection. In other words, digital virtuality has become as pervasive and as invisible as air.

Internet Cloud

The diagram at Figure 2 corresponds quite well with the various ‘internet clouds’ described in a 1999 article9 by Jessie Holliday Scanlon and Brad Wieners:

When it comes to drawing the Internet, the icon of choice – from the MIT Media Lab to trade-show floors, from Intel 's marketing blitzes to the PowerPoint slides of Robertson Stephens analysts – is a cloud.’

Ask the founders of the Net about the cloud, they say, and it quickly becomes apparent that the Net cloud is as old as the Net itself.

"As this Internet was being conceived, diagrams would be drawn to illustrate some design idea," testifies Net architect Bob Taylor. "Some used cloudlike sketches to represent the Internet itself while focusing on other things, like servers or gateways. Variations of these early diagrams ultimately made their way into the literature."

Vint Cerf, co-creator of TCP/IP, the language of networked computers and often cited as one of the Fathers of the Internet, is also comfortable with the idea of a cloud:

‘We always drew networks as amoeba-like things because they had no fixed topology and typically covered varying geographic areas.’

So, say the authors, ‘in short, no one needs to know the exact route their data will take to get from point to point. Everything is fine as long as it comes out of the cloud at the correct address.’ The authors conclude their article with evidence from novelist William Gibson who ‘first encountered the Net-as-cloud metaphor while preparing for his first video teleconference. He asked the tech guys how the signals would travel across the Net. It's not going across the Net, they told him. It's going through "the cloud" – through the totality of all the phone links in the world.’

The problem, however, is that there is still some dispute as to whether the data is actually travelling at all. I posted a query to the Mapping Cyberspace discussion list managed by Martin Dodgex and provoked a lively conversation. It appears that according to transfer protocol, the data doesn’t ‘leave’ node 1 until after it has ‘arrived’ at node 2 so in a sense it is not going anywhere at all.10 Another interpretation is that since data travels at the speed of light, any time taken occurs not during the journey itself but is added in by the routers, which have to read the packets and send them to the right place, and the modems which have to produce the electric pulses to begin with.11 But then, in a further contradictory complication, it could be said that the data is indeed travelling, only not in a physical sense:

It's worth pointing out a difference between moving data packets and physical objects. Throwing a ball actually moves atoms around. Sending a data-packet doesn't change the location of the atoms of your computer, or any piece of equipment involved. If you want an analogy, data packets are more analogous to ripples in water or sound pressure waves in air. Information isn't transferred by moving matter, but rather by the transfer of temporary states/energy-levels through a conducting medium. At the hardware level, the conductive medium is the matrix/fabric of memory cells, wire interconnections, and transducers (electrical, optical, wireless, and back) within all the telecom equipment. That network at the macro and microscopic levels forms something pretty close to 'digital water', much the same way a river system forms a network.12

Or maybe it is not so much travelling as morphing:

In technical terms data travels through a variety of systems - wireless, in the case of wifi, cellular, satellites, copper wires and fiber optics. The use of a single method of transport is exceptionally rare as the midpoints often involve a mix. Light in fibre optics is commonly converted to some form of electronic signal and than regenerated as light to amplify the signal along the way, etc. So, at given transfer points, a bit of the data may even for a nanosecond have more than one manifestation as the packet is picked up from one element of the network and converted to another, for example in an optical switch. In this regard the "net" is more like a plasma13 than a standard plumbing network of pipes and flows.14

Plasma, water, air and apples

How does the technoetic imagination conceive of all this? The answer may lie partly in fuzzy logic. It is ironic that the essentially bivalent nature of computation – zeros and ones – has generated the complex multivalency of virtual space. Bart Kosko, author of Fuzzy Thinking15, believes that ‘the digital revolution seems to have digitized our minds’ to the point where we can only conceive of the world in binary.

To understand the principle of fuzzy logic it is necessary to overturn some of the essential elements of Western thinking and to look instead at problems like the Buddhist koans which ask seemingly impossible questions such as ‘what did your face look like before you were born?’ or the well-known ‘what is the sound of one hand clapping?’. This esoteric notion may seem a long way from the question as to whether data packets are indeed whizzing around the information superhighway or, in contrast, not travelling at all, but perhaps a story about apples will help to clarify the connection.

Kosko provides an illustration of fuzziness in which a grocer is asked to unpack a box of apples and divide them into two piles, red apples (A) and not-red apples (not-A). She might form two distinct piles plus a third pile hard to define as either red or not-red. Now suppose, says Kosko, the grocer unpacks a new box and this time every apple is equally as not-red as it is red. Now the third pile becomes the only pile and contains neither A nor not-A. In this box, all the fruit meet the criterion A=not-A. Perhaps some apples are 80% red, others may be 10% red. Via the same kind of experiment, we can also come to understand that grey is not a diluted form of black or white, but that black and white are both special cases of grey. In other words, fuzziness, or partiality, is the norm, and multivalence reduces to bivalence only in extreme cases.16

By applying fuzzy logic to the discussion of whether or not data packets are actually travelling, it quickly appears that the question is irrelevant since the evidence seems to indicate that, by default, they are both A and not-A. They are between routers at the same time as they are travelling from one to the next – in fact they seem to be everywhere and nowhere. One might assert therefore that the default state of data packets is A=not-A.

It is a small step from here to conclude that the data is in fact its own environment as well. Is this a quantum space perhaps? Sadly, my limited understanding of physics will not allow me to pursue that route of enquiry. However, whether it most resembles water, plasma or air, the most important feature of this A=not-A environment is that it contains ripples which are both comprised of data and which also transport it.

Air and Breath

Movement in air, ripples or other manifestations, is key to this analysis, and it is the notion of wind which brings the discussion full circle with a return to David Abram’s interpretations of the shamanic:

For the Navajo, the Air – particularly in its capacity to provide awareness, thought and speech – has properties that European alphabetical civilisation has traditionally ascribed to an interior, individual human ‘mind’ or ‘psyche’. Yet by attributing these powers to the Air, and by insisting that the ‘Winds within us’ are thoroughly contiguous with the Wind at large – with the invisible medium in which we are immersed (my italics) – the Navajo elders suggest that that which we call the ‘mind’ is not ours, is not a human possession. Rather, mind as Wind is a property of the encompassing world, in which humans – like all other beings – participate.xviii

This seems to be very close to Shunryu Suzuki’s description of inhaling and exhaling through a swinging door. And the Greeks, too, connected the soul, the mind, and the breath through the term psyche and through pneuma, meaning air, wind and breath, and also spirit. In Latin, anima means both breath and wind. According to Abram, ‘we find an identical association of the ‘mind’ with the ‘wind’ and the ‘breath’ in innumerable ancient languages.’17 Air, he proposes, is not just the unseen common medium of our existence, but is that which invisibly joins us to other animals, to plants, and to the landscape itself.

I began this paper with the question: ‘Does virtual space have some kind of atmospheric materiality that is, perhaps, something like air?’ My brief excursion into some possible responses to that enquiry has only served to generate more questions, although since I am a newcomer to phenomenology it is possible that I am treading over much worn ground, so elucidation on any of my comments here is warmly welcomed.

My instinct, at this very early stage of my research, is that our digital bivalency has brought us this far, but from here we must proceed on foot through the fuzzy ripples of a multivalent universe where all apples are A=not-A and uncertainty is the comfortable norm. Is this a question of the two candlesticks trompe d’oeil? Is it time now to switch focus? Is digital virtuality simply a rediscovery of the pneuma that all species inhabit, making visible and usable what we could not see before, like glimpses of exposed motes caught in the sunlight?

There is no doubt that the ‘internet cloud’ is the most intensely compelling environment of the contemporary world. Notions of addiction and other psychological analyses hardly begin to deconstruct the intensely powerful phenomenon of connectedness as we experience it online. We must turn to literature and philosophy to find descriptions which come even close to that experience. I have written about this elsewhere in relation to the writings of Thoreau, Bachelard, and others, but will provide here the example of Shakespeare’s last play The Tempest wherein Caliban, the ‘savage and deformed Slave’, describes the pull of virtuality which permeates the island where he is kept captive:

Be not affeard, the Isle is full of noyses,

Sounds, and sweet aires, that giue delight and hurt not: Sometimes a thousand twangling Instruments

Will hum about mine eares; and sometime voices,

That if I then had wak'd after long sleepe,

Will make me sleepe againe, and then in dreaming,

The clouds methought would open, and shew riches

Ready to drop vpon me, that when I wak'd

I cri'de to dreame againe18

Is Caliban describing moving to and fro through Suzuki’s swinging door? When David Abram writes of an ‘alien gaze infinitely more lucid and precise than my own’, is he staring through that same portal? Both images include A and not-A, two bivalent constructs are offered, but the implications are that each speaker longs to reconcile them and breathe only the air of the limitless world.

Has the computer re-opened a long-closed doorway to an all-encompassing virtuality, an A=not-A universe wherein a different kind of consciousness is in operation, where the winds of Bachelard’s immense cosmic house equate with the Navajo’s ‘mind as Wind’? Where virtuality, like air, is a property of the encompassing world, in which humans – like all other beings – participate? The invisible medium in which we are all immersed?

Such questions cannot be answered by a single writer, philosopher, computer scientist, or artist. They can only be properly framed within the A=not-A arena of transdisciplinarity and that is where this work must continue to be developed, challenged and explored.

First Published as Thomas, S. “Virtuality and Air”, Altered States: transformations of perception, place, and performance, by The Liquid Press, University of Plymouth, 2005

FTP Abbreviation of File Transfer Protocol, the protocol used on the Internet for sending files.

Thomas, S 2004, Hello World, Raw Nerve Books, York. P.104

Abram, D. 1997, The Spell of the Sensuous, Vintage, New York, P.24.

Bachelard, G 1958, The Poetics of Space, Beacon Press, P.51.

Thomas, Hello World, P.264.

http://www.cybergeography.org/atlas/superjanet4_topology_large.gif (image as of March, 2001) vii http://www.mti.dmu.ac.uk/~sthomas/

now offline

Leder, D 1990, The Absent Body , University of Chicago Press, Chicago, P.170.

Thanks to Martin Dodge for this reference http://www.thestandard.com/article/display/1,1151,5466,00.html July 09, 1999

Mapping Cyberspace discussion list http://www.jiscmail.ac.uk/lists/mapping-cyberspace.html

Post from Dena Attar to Mapping Cyberspace 29/5/05

Post from Ben Spigel to Mapping Cyberspace 29/5/05

Post from Michael Okincha to Mapping Cyberspace 31/5/05

According to Wikipedia, plasma (as understood in physics and chemistry) is an energetic gas-phase state of matter, often referred to as "the fourth state of matter". (In medical terms, it is used as a transport medium.) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plasma_physics xv Post from Oguchi Nkwocha to Mapping Cyberspace 29/5/05 xvi Kosko, B 1993, Fuzzy Thinking, HarperCollins, London.

Kosko, B 1993, Fuzzy Thinking, HarperCollins, London

Kosko, Fuzzy Thinking, P.28.

Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous, P.237.

Shakespeare, W. The Tempest III.ii.130–138.